Disciplined Parametrized Programming¶

Note: DPP requires CVXPY version 1.1.0 or greater.

Parameters are

symbolic representations of constants. Using parameters lets you modify the

values of constants without reconstructing the entire problem. When your

parametrized problem is constructed according to Disciplined Parametrized

Programming (DPP), solving it repeatedly for different values of the

parameters can be much faster than repeatedly solving a new problem.

You should read this tutorial if you intend to solve a DCP or DGP problem many times, for different values of the numerical data, or if you want to differentiate through the solution map of a DCP or DGP problem.

What is DPP?¶

DPP is a ruleset for producing parametrized DCP or DGP compliant problems that CVXPY can re-canonicalize very quickly. The first time a DPP-compliant problem is solved, CVXPY compiles it and caches the mapping from parameters to problem data. As a result, subsequent rewritings of DPP problems can be substantially faster. CVXPY allows you to solve parametrized problems that are not DPP, but you won’t see a speed-up when doing so.

The DPP ruleset¶

DPP places mild restrictions on how parameters can enter expressions in DCP and DGP problems. First, we describe the DPP ruleset for DCP problems. Then, we describe the DPP ruleset for DGP problems.

DCP problems. In DPP, an expression is said to be parameter-affine if it does not involve variables and is affine in its parameters, and it is parameter-free if it does not have parameters. DPP introduces two restrictions to DCP:

Under DPP, all parameters are classified as affine, just like variables.

Under DPP, the product of two expressions is affine when at least one of the expressions is constant, or when one of the expressions is parameter-affine and the other is parameter-free.

An expression is DPP-compliant if it DCP-compliant subject to these two

restrictions. You can check whether an expression or problem is DPP-compliant

by calling the is_dcp method with the keyword argument dpp=True (by

default, this keyword argument is False). For example,

import cvxpy as cp

m, n = 3, 2

x = cp.Variable((n, 1))

F = cp.Parameter((m, n))

G = cp.Parameter((m, n))

g = cp.Parameter((m, 1))

gamma = cp.Parameter(nonneg=True)

objective = cp.norm((F + G) @ x - g) + gamma * cp.norm(x)

print(objective.is_dcp(dpp=True))

prints True. We can walk through the DPP analysis to understand why

objective is DPP-compliant. The product (F + G) @ x is affine under DPP,

because F + G is parameter-affine and x is parameter-free. The difference

(F + G) @ x - g is affine because the addition atom is affine and both

(F + G) @ x and - g are affine. Likewise gamma * cp.norm(x) is affine

under DPP because gamma is parameter-affine and cp.norm(x) is

parameter-free. The final objective is then affine under DPP because addition is

affine.

Some expressions are DCP-compliant but not DPP-compliant. For example, DPP forbids taking the product of two parametrized expressions:

import cvxpy as cp

x = cp.Variable()

gamma = cp.Parameter(nonneg=True)

problem = cp.Problem(cp.Minimize(gamma * gamma * x), [x >= 1])

print("Is DPP? ", problem.is_dcp(dpp=True))

print("Is DCP? ", problem.is_dcp(dpp=False))

This code snippet prints

Is DPP? False

Is DCP? True

Just as it is possible to rewrite non-DCP problems in DCP-compliant ways, it is also possible to re-express non-DPP problems in DPP-compliant ways. For example, the above problem can be equivalently written as

import cvxpy as cp

x = cp.Variable()

y = cp.Variable()

gamma = cp.Parameter(nonneg=True)

problem = cp.Problem(cp.Minimize(gamma * y), [y == gamma * x])

print("Is DPP? ", problem.is_dcp(dpp=True))

print("Is DCP? ", problem.is_dcp(dpp=False))

This snippet prints

Is DPP? True

Is DCP? True

In other cases, you can represent non-DPP transformations of parameters

by doing them outside of the DSL, e.g., in NumPy. For example,

if P is a parameter and x is a variable, cp.quad_form(x, P) is not

DPP. You can represent a parametric quadratic form like so:

import cvxpy as cp

import numpy as np

import scipy.linalg

n = 4

L = np.random.randn(n, n)

P = L.T @ L

P_sqrt = cp.Parameter((n, n))

x = cp.Variable((n, 1))

quad_form = cp.sum_squares(P_sqrt @ x)

P_sqrt.value = scipy.linalg.sqrtm(P)

assert quad_form.is_dcp(dpp=True)

As another example, the quotient expr / p is not DPP-compliant when p is

a parameter, but this can be rewritten as expr * p_tilde, where p_tilde is

a parameter that represents 1/p.

DGP problems. Just as DGP is the log-log analogue of DCP, DPP for DGP is the log-log analog of DPP for DCP. DPP introduces two restrictions to DGP:

Under DPP, all positive parameters are classified as log-log-affine, just like positive variables.

Under DPP, the power atom

x**p(with basexand exponentp) is log-log affine as long asxandpare not both parametrized.

Note that for powers, the exponent p must be either a numerical constant

or a parameter; attempting to construct a power atom in which the exponent

is a compound expression, e.g., x**(p + p), where p is a Parameter,

will result in a ValueError.

If a parameter appears in a DGP problem as an exponent, it can have any

sign. If a parameter appears elsewhere in a DGP problem, it must be

positive, i.e., it must be constructed with cp.Parameter(pos=True).

You can check whether an expression or problem is DPP-compliant

by calling the is_dgp method with the keyword argument dpp=True (by

default, this keyword argument is False). For example,

import cvxpy as cp

x = cp.Variable(pos=True)

y = cp.Variable(pos=True)

a = cp.Parameter()

b = cp.Parameter()

c = cp.Parameter(pos=True)

monomial = c * x**a * y**b

print(monomial.is_dgp(dpp=True))

prints True. The expressions x**a and y**b are log-log affine, since

x and y do not contain parameters. The parameter c is log-log affine

because it is positive, and the monomial expression is log-log affine because

the product of log-log affine expression is also log-log affine.

Some expressions are DGP-compliant but not DPP-compliant. For example, DPP forbids taking raising a parametrized expression to a power:

import cvxpy as cp

x = cp.Variable(pos=True)

a = cp.Parameter()

monomial = (x**a)**a

print("Is DPP? ", monomial.is_dgp(dpp=True))

print("Is DGP? ", monomial.is_dgp(dpp=False))

This code snippet prints

Is DPP? False

Is DGP? True

You can represent non-DPP transformations of parameters by doing them outside of CVXPY, e.g., in NumPy. For example, you could rewrite the above program as the following DPP-complaint program

import cvxpy as cp

a = 2.0

x = cp.Variable(pos=True)

b = cp.Parameter(value=a**2)

monomial = x**b

Repeatedly solving a DPP problem¶

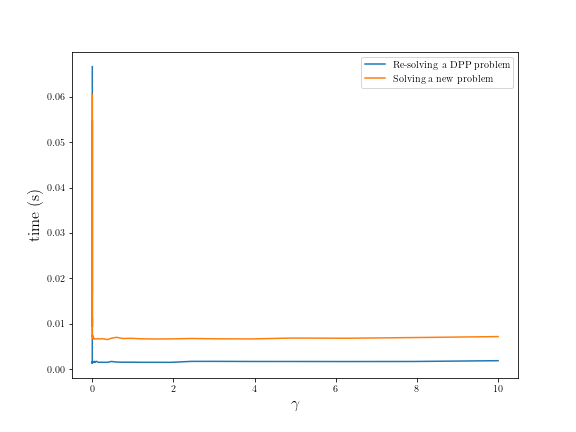

The following example demonstrates how parameters can speed-up repeated solves of a DPP-compliant DCP problem.

import cvxpy as cp

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import time

n = 15

m = 10

numpy.random.seed(1)

A = numpy.random.randn(n, m)

b = numpy.random.randn(n)

# gamma must be nonnegative due to DCP rules.

gamma = cp.Parameter(nonneg=True)

x = cp.Variable(m)

error = cp.sum_squares(A @ x - b)

obj = cp.Minimize(error + gamma*cp.norm(x, 1))

problem = cp.Problem(obj)

assert problem.is_dcp(dpp=True)

gamma_vals = numpy.logspace(-4, 1)

times = []

new_problem_times = []

for val in gamma_vals:

gamma.value = val

start = time.time()

problem.solve()

end = time.time()

times.append(end - start)

new_problem = cp.Problem(obj)

start = time.time()

new_problem.solve()

end = time.time()

new_problem_times.append(end - start)

plt.rc('text', usetex=True)

plt.rc('font', family='serif')

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

plt.plot(gamma_vals, times, label='Re-solving a DPP problem')

plt.plot(gamma_vals, new_problem_times, label='Solving a new problem')

plt.xlabel(r'$\gamma$', fontsize=16)

plt.ylabel(r'time (s)', fontsize=16)

plt.legend()

Similar speed-ups can be obtained for DGP problems.

Sensitivity analysis and gradients¶

Added in version 1.1.0: This feature requires CVXPY version 1.1.0 or greater

An optimization problem can be viewed as a function mapping parameters

to solutions. This solution map is sometimes differentiable. CVXPY

has built-in support for computing the derivative of the optimal variable

values of a problem with respect to small perturbations of the parameters

(i.e., the Parameter instances appearing in a problem).

The problem class exposes two methods related to computing the derivative.

The derivative evaluates

the derivative given perturbations to the parameters. This

lets you calculate how the solution to a problem would change

given small changes to the parameters, without re-solving the problem.

The backward method

evaluates the adjoint of the derivative, computing the gradient of the solution

with respect to the parameters. This can be useful when combined with

automatic differentiation software.

The derivative and backward methods are only meaningful when the problem contains parameters. In order for a problem to be differentiable, it must be DPP-compliant. CVXPY can compute the derivative of any DPP-compliant DCP or DGP problem. At non-differentiable points, CVXPY computes a heuristic quantity.

Example.

As a first example, we solve a trivial problem with an analytical solution,

to illustrate the usage of the backward and derivative

functions. In the following block of code, we construct a problem with

a scalar variable x and a scalar parameter p. The problem

is to minimize the quadratic (x - 2*p)**2.

import cvxpy as cp

x = cp.Variable()

p = cp.Parameter()

quadratic = cp.square(x - 2 * p)

problem = cp.Problem(cp.Minimize(quadratic))

Next, we solve the problem for the particular value of p == 3. Notice that

when solving the problem, we supply the keyword argument requires_grad=True

to the solve method.

p.value = 3.

problem.solve(requires_grad=True)

Having solved the problem with requires_grad=True, we can now use the

backward and derivative to differentiate through the problem.

First, we compute the gradient of the solution with respect to its parameter

by calling the backward() method. As a side-effect, the backward()

method populates the gradient attribute on all parameters with the gradient

of the solution with respect to that parameter.

problem.backward()

print("The gradient is {0:0.1f}.".format(p.gradient))

In this case, the problem has the trivial analytical solution 2*p, and

the gradient is therefore just 2. So, as expected, the above code prints

The gradient is 2.0.

Next, we use the derivative method to see how a small change in p

would affect the solution x. We will perturb p by 1e-5, by

setting p.delta = 1e-5, and calling the derivative method will populate

the delta attribute of x with the change in x predicted by

a first-order approximation (which is dx/dp * p.delta).

p.delta = 1e-5

problem.derivative()

print("x.delta is {0:2.1g}.".format(x.delta))

In this case the solution is trivial and its derivative is just 2*p, so we

know that the delta in x should be 2e-5. As expected, the output is

x.delta is 2e-05.

We emphasize that this example is trivial, because it has a trivial analytical

solution, with a trivial derivative. The backward() and forward()

methods are useful because the vast majority of convex optimization problems

do not have analytical solutions: in these cases, CVXPY can compute solutions

and their derivatives, even though it would be impossible to derive them by

hand.

Note. In this simple example, the variable x was a scalar, so the

backward method computed the gradient of x with respect to p.

When there is more than one scalar variable, by default, backward

computes the gradient of the sum of the optimal variable values with respect

to the parameters.

More generally, the backward method can be used to compute the gradient of

a scalar-valued function f of the optimal variables, with

respect to the parameters. If x(p) denotes the optimal value of

the variable (which might be a vector or a matrix) for a particular value of

the parameter p and f(x(p)) is a scalar, then backward can be used

to compute the gradient of f with respect to p. Let x* = x(p),

and say the derivative of f with respect to x* is dx. To compute

the derivative of f with respect to p, before calling

problem.backward(), just set x.gradient = dx.

The backward method can be powerful when combined with software for

automatic differentiation. We recommend the software package

CVXPY Layers, which provides

differentiable PyTorch and TensorFlow wrappers for CVXPY problems.

backward or derivative? The backward method should be used when

you need the gradient of (a scalar-valued function) of the solution, with

respect to the parameters. If you only want to do a sensitivity analysis,

that is, if all you’re interested in is how the solution would change if

one or more parameters were changed, you should use the derivative

method. When there are multiple variables, it is much more efficient to

compute sensitivities using the derivative method than it would be to compute

the entire Jacobian (which can be done by calling backward multiple times,

once for each standard basis vector).

Next steps. See the introductory notebook on derivatives.